More Americans used to vote in midterm elections than presidential elections

Here’s a surprising fact about US history: more Americans used to vote in midterm congressional elections than bothered to vote in presidential election years. Today the trend is the exact opposite.

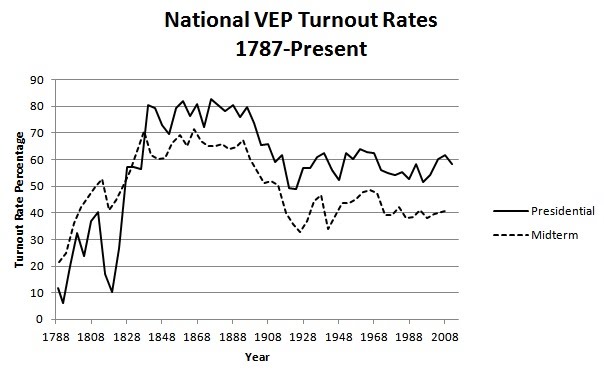

Check out this graph that shows election turnout from the founding of America onward. As you can see, midterm elections were more popular than presidential elections up until about the middle of the 19th century. Why was that?

Early Americans viewed presidents as less powerful than Congress and therefore it was more important to vote for congress than it was for whoever the president was. And it’s not hard to see why: consider that Article One, Section One of the US Constitution did not establish the presidency but instead established Congress. It doesn’t even mention the presidency until later. It reads:

All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.

In early American history, voters recognized that under the US Constitution, Congress has the power to write laws, the president doesn’t. Congress has the power to establish taxes, the president doesn’t. Congress has the power to declare war, the president doesn’t. More recently in American history, the presidency has become more powerful and Congress has ceded some of its power to the White House, a development that remains very controversial among constitutional scholars and historians.

The fact that more Americans used to vote in midterm congressional elections than in presidential elections becomes more interesting when you consider that initially at first, Americans didn’t have the right to vote for who their senators were. Until the 17th Amendment passed in 1913, US Senators were elected by each state’s legislature. So Americans would vote for their Congressman in the House of Representatives, and their state legislators, who would in turn elect their Senators for them.

Of course, during the period of time that midterm elections were more popular than presidential elections, it’s important to remember who exactly was and wasn’t allowed to vote. Although turnout rates were often high (80% in 1840!), this only counts the number of people who voted as a percent of those eligible to vote in the first place. Women and people of color did not get the ability to vote until later. Although some states had individually given women the right to vote earlier, the 19th Amendment did not guarantee women the franchise in all states until it was adopted in 1920. Similarly, the 15th Amendment was adopted in 1870, which (in promise at least) gave people of color the right to vote. But practically speaking, it wasn’t until the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-20th Century that that promise became a reality for many:

Although ratified on February 3, 1870, the promise of the 15th Amendment would not be fully realized for almost a century. Through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests and other means, Southern states were able to effectively disenfranchise African Americans. It would take the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 before the majority of African Americans in the South were registered to vote.

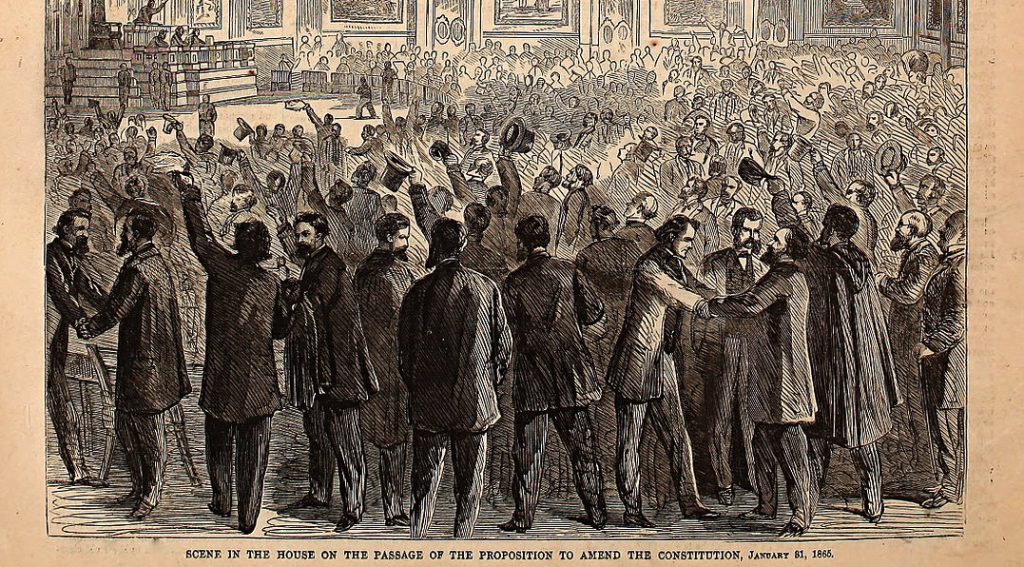

There was however a brief period of time after the Civil War and the end of slavery but before racist Jim Crowe laws were adopted in the South that saw the temporary rise of African American voters. Read our related article for more about this period called Reconstruction: 23 African Americans Were Elected to Congress Before the Civil Rights Movement.

History aside, voting in midterm congressional elections is critically important.